Transmission 6.085.251

Translation by Carole M. Bowcutt

Simon,

Please find attached the specifications for the next operation. Route any questions or feedback through standard channels and follow the regular procedures. Note, for this operation, there are no conditions for success. This is not an oversight; it’s by design.

Monitor the situation and alert me of any irregularities outside the parameters established in the specifications.

- Sadie

Chapter One

8:05:32 a.m.

So spake the grisly Terror —John Milton

Nick Carson carried his shopping basket to the front of the store. Two boxes of Tuna Helper, canned tuna, a half-gallon of milk, and a few Moon Pies—enough food to last him through the weekend.

He had nowhere pressing to be. Back at his apartment, most of his dishes were dirty in the sink. Laundry scattered in the bedroom and bathroom. The bathroom itself could use a good cleaning, but none of that was on his to-do list. Hell, he didn’t even have a to-do list. His plans for the day involved going home, heating two burritos in the microwave, and drinking milk straight from the carton. Maybe he’d see if PBS had any cartoons in their lineup.

Maybe he could lose himself in the memory of happier times.

Pulling the hood of his sweatshirt lower, he made his way toward the front of the store. With his head down, it was easier to avoid the eyes of the other shoppers.

Of course, it wasn’t their eyes he wanted to avoid.

A woman stood in line at the first check stand. She wore white sneakers and faded purple sweats. Two small children—a boy and a girl—stood nearby. The boy clutched a bag of peanut M&Ms and the girl clung to her mother’s legs as if holding down a hot air balloon. Plucking items from her grocery cart, the woman added them to a massive pile on the conveyor belt. The little girl needed a nose wipe.

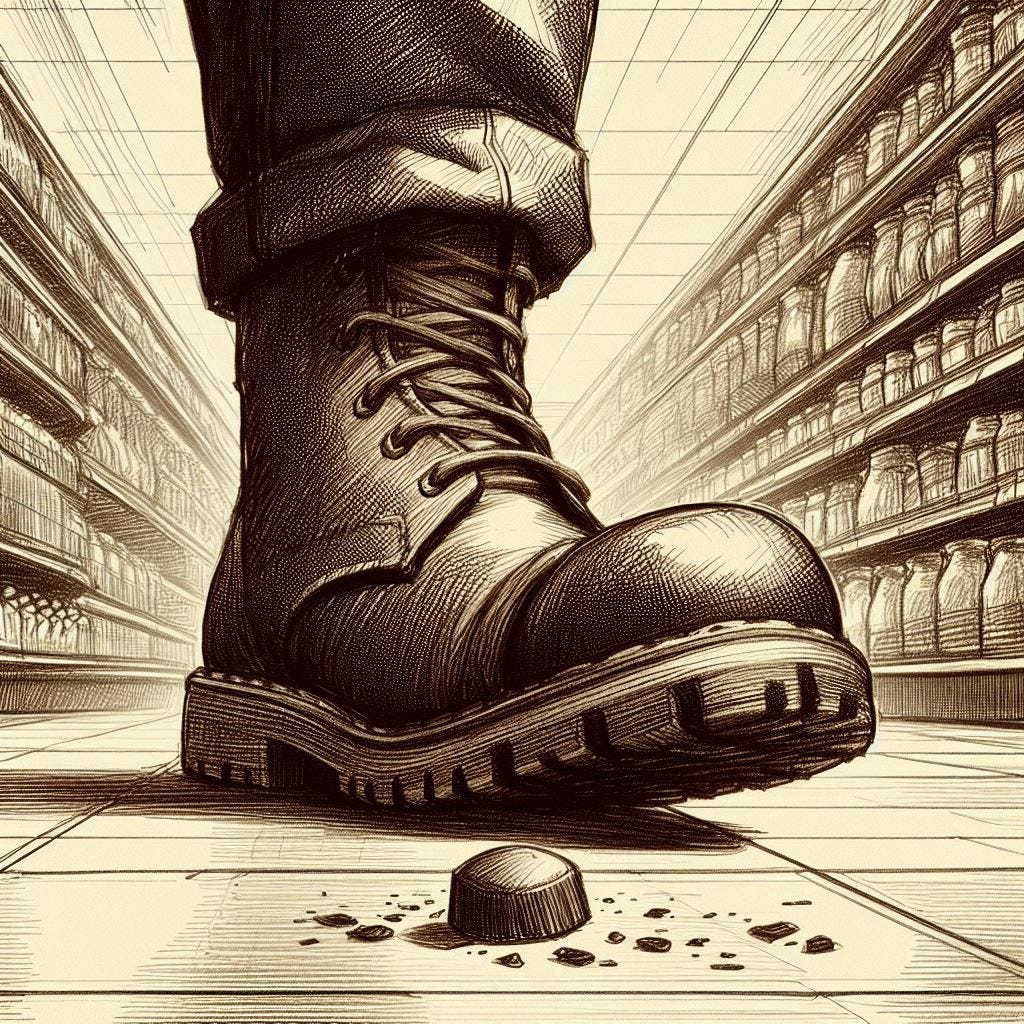

The boy shook his bag of M&Ms, spilling the candy into his hand. One of the pieces fell to the floor with a crack and rolled toward Nick. Spying the loose candy, the girl gave a squeal of delight, let go of her mother’s leg, and chased after the rolling chocolate.

Nick stopped the candy under his boot before it could roll beneath a cardboard bin filled with pumpkins. The girl pulled up short, looking first at Nick’s boot and then up at his face. Nick kept his head down. He could barely see her eyes from under his hood—eyes that reminded him of a deer, wide and brown and wet. Snot glistened on her upper lip.

Nick pressed down, crushing the candy between his boot and the floor. Shards of orange candy-coated shell sprayed out like a smashed bug on a windshield.

The little girl’s eyes widened even more. Nick walked past her to the next check stand.

A group of teenagers waited in line. If they had attended his school, he didn’t recognize them. They were probably freshmen or sophomores. Sagging pants and untied shoes. Hands clutching sodas and white sacks from the bakery. A quick run for snacks before school started. Not a lot of items, but they were likely all paying separately. Too many transactions.

One more open check stand. Pressing his luck, he carried his basket to the end of the row. An elderly man clutched a pen attached to a silver-beaded chain. He wrote carefully in his checkbook—his hand trembling. He didn’t look to be in a hurry, but only a few items remained on the conveyor. Nick dropped his basket on the belt and set down a plastic divider.

The girl working the register laughed at something the old man said. It wasn’t a courtesy laugh or a laugh made bigger just for show. It was an honest laugh. One that made you want to know the joke so you could join in.

Nick raised his head with care until he could just see the girl’s face. He didn’t want to see more.

She looked nineteen, maybe twenty—a year older than Nick. She had light brown hair pulled back in a braid, and her eyes scrunched together when she smiled. She wore no makeup. She hadn’t gone to his high school, or he would have known her, but something about her looked familiar. A distant memory buried deep. He hadn’t seen her here before. Maybe she went to one of the other three high schools in the valley, and he’d seen her in passing at a football or basketball game.

The girl watched the man write his check, then glanced in his direction. Nick looked away.

He knew what she saw with that glance—what he looked like. Ragged Levi’s and worn shoes, a thin and scraggly beard, eyes peeking out from inside the shadows of his hoodie. People looked at him and then looked again—a secret sideways glance—like he might have a knife hidden in his pocket.

Probably on drugs. Poor life choices. He deserves what he gets.

He waited for that second glance from the girl, the nervous look or the one that carried judgments. It never came. The elderly man ripped his check from his checkbook. “See if that one takes,” he said, and the girl laugh again.

The man passed over his check, but the girl dropped it before she could place it in the register. Before he could look away, she bent down, and the symbols came into view.

The goddamn symbols.

He didn’t want to see them. If he’d been paying better attention, he’d have looked away. But it was like driving past a wreck on the freeway. When you see the twisted steel and broken glass that used to be a car, you can’t help but look.

Six inches above the cashier’s head and a little to the right, there was a rift in the space above her head. Symbols of pale light floated on the other side, with a wide expanse of mist as a backdrop. Small and polished, the symbols looked like ivory and ice. Three columns, eleven rows, two symbols—repeated.

Just like always; just like everyone.

ФФД

ДДД

ДФФ

ДДД

ФДД

ФДД

ДДД

ДДД

ДДД

ДДД

ДДД

Nick knew the symbols well, and he knew what they meant—what they meant to him and what they meant to the girl.

He stared at the floor and fought the rising anger.

He’d missed a symbol, that’s all. One of the later ones that gave the girl more time. Much more time.

He could walk out of the store. He could go home, eat his burritos, and watch his cartoons. He’d figured wrong, that’s all.

But he hadn’t. He’d done this too many times. He didn’t make mistakes—not when it came to the symbols.

The girl started scanning his groceries. She smiled and said something, but the words didn’t register.

Nick said nothing and kept his head low. When she told him the amount, he dropped a fist full of bills on the counter, grabbed his sack, and left the store.

He threw his groceries in the backseat of his Toyota Tercel, slammed the door, lit a cigarette, and leaned against the car. He sucked smoldering tobacco deep into his lungs. The smoke punched the back of his throat, and he welcomed the slow, mellowing buzz. His shaking hands steadied. His breathing slowed, and he offered the cigarette’s ashes to the breeze.

He tugged at the hairs on his chin. They were getting long. He should shave.

The sun had burned off the frost and early morning chill. The autumn air felt cool on his face, but the cloudless sky carried the hope of a warm day. He looked back toward the store. Large green letters spelled out Lee’s Grocery above two banks of sliding doors.

Walk away. Don’t look back. This isn’t your fault and it’s not your job. You don’t have to save everyone.

He spit onto the asphalt.

How long had he been doing this? Two years? Three? It felt longer.

He pulled at the cigarette, held his breath, released.

Three years. He’d been part of a family then. Had friends. Chores on Saturday. Church on Sunday. His sisters’ soccer games on chilly weekday nights. But that was a different time. It has become the echo of a dream from another life.

Memories played out in his mind like a flickering home movie. Smiling faces around a half-eaten casserole. A cushion fort in the living room. An imaginary jungle safari through Willow Park. Lyrics from a gentle time.

And now . . . a dropout. He hadn’t finished his senior year. He had a dirty apartment and a second-hand bike. Work when he could find it. Jobs here and there for as long as he could hold them.

And guilt. Always the guilt that woke him in the darkness of the early morning and made him fight for breath.

Nick finished his cigarette. One of the baggers, pushing a line of carts toward the store, eyed him warily. The distance was too great to see any symbols. Nick flicked the butt in the kid’s direction. Glaring, Nick lit another cigarette. The bagger pretended not to see and walked back into the store.

Maybe a manager would come out and tell him to stop loitering. Tell him to get the hell on his way. Nick waited for it. Hoped for it. He’d have none of it, of course. He’d push or shove. Get into a fight. Maybe swing a fist. If they called the police, he wouldn’t have to make the damn choice. The police knew him well, and he knew them. He’d spend the weekend in county jail.

But the manager didn’t come, so Nick continued to smoke and flick his ash.

I taught you to do the right thing.

It was his mother’s voice in his head. He hadn’t seen her in over eight months, but he couldn’t escape her words. They came back to him when life seemed the darkest and made it darker yet.

I taught you to do the right thing.

The right thing.

In all his life, he had never found it hard to do the right thing. Doing the right thing was easy.

Deciding what the right thing was . . . that was the real pisser.

The asphalt grew warmer under the bright sun. He sucked smoke into his lungs and thought of the girl inside Lee’s Marketplace. Her laughter echoed in the corners of his memory.

The girl with the brown hair who would live to see the sun set, but not rise.

She’d be dead before dawn.

SO GOOD!!!!! I cannot wait to read more. I am definitely hooked. Excellent!

Wow - what an opening. I'm hooked. Now to wait a whole week...