Transmission

Translation by Andrea Cade

Sadie,

I’m trying to better understand what we are gaining from this experiment. This is not an appeal to terminate prematurely, by any means. To ensure we’re getting the most out of it, I’m trying to understand our objectives.

We must be learning something, or we would have terminated long ago. But what? We see the same behavior from Nick over and over again. He sees a person with a short timer, and he tries to save that person. If he succeeds, he is happy. If he fails, he is sad. It feels like we have gathered enough information to establish a pattern.

In reviewing the past few operations, I see that each time the cost of saving a person has risen. More must be done. More must be sacrificed. Nick must give more of himself to succeed. Is this intentional?

Is our intent to break him? Or find the point at which he surrenders?

I guess if we determine that point, it may give insight into the value of a life.

-Simon

It is well to think well; it is divine to act well. —Horace Mann

Celeste drove east on Highway 30 into Logan.

“Turn left when you get to Tenth West,” Nick said.

He pulled Celeste’s phone from his pocket and turned it on.

Celeste had been spotted in Preston. If she’d been identified as his kidnap victim, there would be an explosion of missed calls, texts, and voicemails from friends and family. He had to know if the police were looking for her car.

Of course, if they were looking for her car, they were also looking for her phone. Turning the phone on was a significant risk. Leaving the phone off was a significant risk.

He rubbed at his right temple. Maybe this is exactly how a person’s day should go when that person snatches another human being.

The phone went through its initial startup routines. He asked Celeste how to get past the security screen, then waited until he saw the bars of the phone lock-in, letting him know the phone had reception. He counted to sixty.

No missed calls. No phone messages. Four texts.

It felt wrong, but he scrolled through them. Two texts from the same person asking her when she got off work. Another text from a different person, asking where they were meeting for the game tonight. A text from somebody asking if Celeste could cover a shift next Tuesday.

Sorry, buddy, there’s not going to be a shift next Tuesday.

He powered down the phone.

They drove past a family raking leaves in their front yard. A father and mother, two girls and a boy, and a lot of flannel. The boy looked bored, and one of the girls sat on her heels and pouted, but other than that, it was a perfect snapshot of a happy suburban family. Honest work in the yard. Preparing the homestead for the gathering storms of a winter that would never come. The timers were identical.

All five would be dead eighteen minutes after one o’clock.

Celeste stopped at the light at Tenth West. The block stood surprisingly calm. Elsewhere sirens pealed, and police officers scrambled, hunting for an evil man and two innocent victims. But here, at the corner of Tenth West and Highway 30, the air was still. The grass and cement and trees were quiet.

Two college-aged girls waited for the light to change so they could cross the street. A family poured from a car, two young children running into LW’s Truck Stop. Several people stood next to their cars, filling their vehicles with gas. A bald man squeegeed his windshield with a window wiper.

Every timer identical.

Nick saw a girl staring out of the back window of a Volkswagen Jetta, watching her dad pump gas. A girl with blond hair. Eight. Maybe Nine. From this distance, she looked like his sister Beth. She turned in the car and disappeared.

“Turn right.”

“You said left. I’m already in the left-turning lane.”

“Turn right, goddammit.”

Celeste changed her blinker. She backed up, inched over, and switched lanes. When the light turned green, she drove south.

“It’s probably not the best idea to be breaking traffic laws,” Celeste said. “You don’t want to get pulled over right now.”

Nick made no reply. Besides, the police had more weighty issues than a girl violating a minor traffic law.

“Where are we going?”

He said nothing, only stared out the window, looking at each street sign as it passed.

“Turn left. There at the school.”

Celeste turned. He directed her left and then right twice.

“Pull in there—at Willow Park.” He motioned to a parking lot away from other cars.

Celeste brought the vehicle to a stop. Nick felt exposed. Kids raced around under towering cottonwood trees. Parents watched from benches or from the grass. One group ate at picnic tables under a bowery, laughter bounding up and out. Two teenage boys with mitts threw a baseball around, the ball snapping into their waxy leather gloves.

Identical timers.

Nick got out of the car and sat behind Celeste’s seat, so he could see the house better. The home he’d been born in—on 350 West. The home where his family still lived.

Motion in a car parked a little down the street caught Nick’s attention. A late-model blue Chevy. Tinted windows. It sat parked in front of the Skibys’ house. The Skibys only owned a mini-van and a motor scooter.

The police.

He could go no closer without significant risk, but he could sit here for a while. Sit and watch. For just a moment.

Nick sat in the back of Celeste’s car and watched his front room window.

*****

Nick sat in the back of the patrol car and watched the front room window.

The blue-and-red lights flashed silently against his house and the surrounding homes. Even the trees across the street at Willow Park flashed blue and red as if screaming his crime in unison. The lights made a rapid pattern—flash flash flash. A quick trio of colors. First blue, then white, then red. They seemed to be saying, Nick’s in trouble. Come and look. Nick’s in trouble. Come and look.

It was late—after two o’clock in the morning—but he had no doubt that the neighborhood would be buzzing, come sunrise. The lights had surely awoken Mr. Talbot, and that meant everybody else would know, right after breakfast. Or maybe even before.

Officer Hill opened the car door. “Come on, Nick. Let’s get you inside.” He reached in and took Nick by the crook of his arm. Nick’s hands were cuffed behind him. Stepping out of the car, he allowed them to lead him to the door.

Officer Fertig rang the doorbell, thumped on the door, and then rang the doorbell a second time. Nick winced at the sharp noises. Far to his right, a dog barked.

Lights flared inside his house, first the bedroom, then the hall, then the living room, and finally the porch light, bathing them all in bright white light.

Nick winced. He preferred darkness to light.

The door opened, and his mother came into view. She didn’t look at the police officers. She didn’t look to see if any neighbors were peeking out from behind curtains.

Her eyes locked with his. A cold look. Empty. He could have been a stranger. He could have been a patch of weeds. A stone.

“Hello, Mrs. Carson,” Officer Hill said. “Sorry to bother you so late at night.”

She broke her gaze with Nick. “It’s not your fault, Officer . . . ” she glanced down at his badge. “Officer Hill.” Her eyes zeroed back to Nick. “You’re not the one causing problems.”

Nick wanted to meet his mother’s gaze. He did what he believed was right. He had nothing to feel ashamed of, and so he would meet his mother’s cold stare with one of his own.

But his gaze fell. He tapped his right shoe against his left shoe. The action left a streak of black against the white rubber top. His feet were still covered in mud.

He liked looking at his feet. Or anybody’s feet. When he stared at feet, he couldn’t see the timers. He didn’t want to see any timers. Not right now. Maybe not ever again.

“We had a report of somebody prowling around some bushes up on 1700 North.” Officer Fertig was new, Nick knew, and this policeman did things by the book. “We arrived on the scene and found your son. He tried running but we gave chase and we were able to apprehend him. He was sneaking around the home of Tim and Judy Lusk. Do you know them?”

Nick felt, rather than saw, the weight of his mother’s gaze and almost took a step back.

“Yes, my son is friends with their daughter Becky. She’s his age. We met her and her family at a school play just last week.”

Nine days, to be exact. He knew all too well the exact time and date. Because of the damn timer.

Becky was a girl in his Chemistry class who had taken an interest in him. She’d given him a shy wave at the play in passing, and Nick’s mom had made a big fuss about it. She insisted Nick introduce her family to Becky’s family after the play ended.

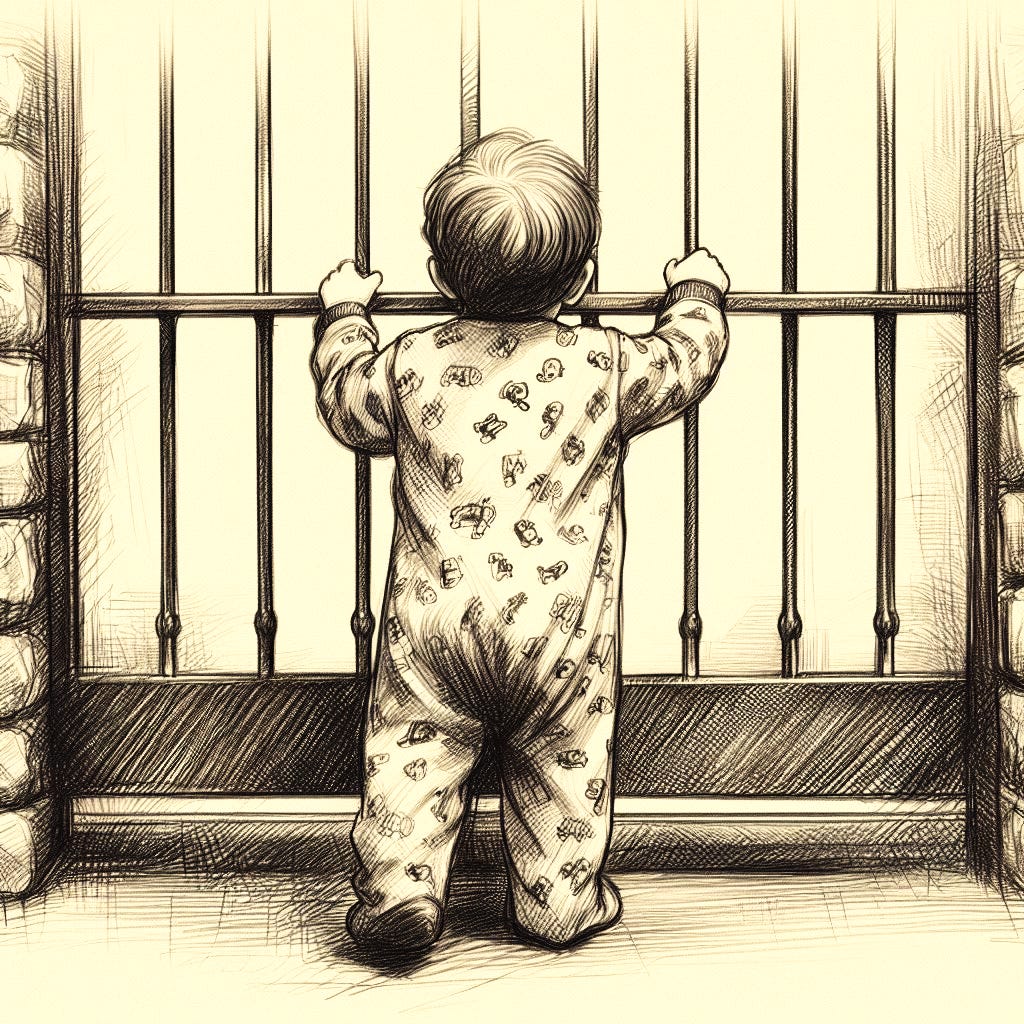

Becky’s family was large . . . Nick wasn’t even sure how many. He took in all the family—all of the timers—in a single glance. Everyone was fine except for the baby. A baby—less than a year old. Not old enough to walk, but old enough to spend the entire conversation trying to free himself from his mother’s arms.

ФФД

ФДФ

ФФФ

ДФД

ФФД

ДДФ

ДФД

ДДД

ДДД

ДДД

ДДД

Ten days. The baby had ten days to live.

The thrill of his power had long worn off by then. He felt wasted and worn thin. Tired of timers. Tired of struggling against death. But the baby . . . the baby smiled a toothy grin and looked so alive. So anxious to get down and explore the world.

He looked again at the rest of the family—the dad who looked drained but had a brightness about him. The mom with friendly eyes. The brothers and sisters had Becky’s shyness, but also a healthy dose of energy. All of them just a little over a week from losing a son and brother.

Nick pictured them on the front row of some church, dressed in black and crying in front of a tiny coffin. His stomach churned, and the spit in his mouth turned foul. He knew then he would try. Just once more.

There was always a once more.

It was easy to befriend Becky. It was easy to find out where she lived. He’d even invited himself over to work on a science project—an invitation that Becky had jumped at eagerly. Nick asked for a tour of the house and saw the bushes in the backyard. He took note and made plans.

He suspected the pool in the backyard. For the past three nights, he’d been hiding out in the bushes. Sleeping during the day when he could. He left school early every day, hiding out, watching the backyard. Saving a life was hard, but he had hope. The closer he could get to a timer reaching zero, the better his chances.

“Is he under arrest?” Mom asked the two police officers. “Maybe a night in jail would help knock some sense into this . . . this boy’s head.”

Nick felt his face go red. She’d paused before she’d said, boy. What had she been going to say? His mother loved him, he knew that. But ever since the accident . . . ever since the timers, things had been different. A distance had grown between them. A wide valley of misunderstanding and hurt.

The two officers exchanged looks. They’d already discussed at length what to do. “We didn’t want to wake up the Lusk family,” Officer Hill said. “We don’t know if they’ll press charges. And where Nick is a minor . . . it gets complicated. We thought maybe you’d like to keep him here and then we can straighten things out in the morning.”

Nick’s mother said nothing for a while. Nick finally raised his eyes. She looked at him but did not see him. Her eyes were focused somewhere just off to the right and she said nothing for a time.

Finally, her mother spoke. “I don’t know that I want him.”

Nick looked back down to his feet and clenched his eyes shut.

“I’m tired of this boy and the hurt he brings this family. I taught him better than this. I taught him to do right.”

The words hung there, in the stillness of the dark.

Officer Hill sighed. “Listen, Mrs. Carson, I know—”

She spun on her heels and was gone, the door left open.

The two officers exchanged a glance, and then Officer Hill undid the handcuffs. “Go on in, Nick,” he said. “We’ll see you in the morning.”

Nick stumbled inside. His mother was gone—probably back to her room. He went downstairs to his own room and sat on the bed. Outside the crickets chirped. The flashing lights of the patrol car stopped. He heard the rise of the engine as the car pulled away from the house, the headlights making a yellow box through the window that moved across his wall, then faded and disappeared.

He sat on the edge of his bed. In her room above, his mother cried. At times, she spoke. Praying, probably. He couldn’t hear the words. Sometimes her voice sounded angry. Other times pleading. Desperate. Mostly he heard grief.

He sat on the edge of the bed and listened to how much pain he’d caused somebody he loved very much. He wanted to cry but he couldn’t. Inside he felt only cold ash. He pulled at his hair and welcomed the pain.

He and Mom fought all the time. Their arguments louder and more intense. More hurtful. She accused him of awful things. He tried to defend himself but couldn’t. He’d started to tell her the truth a dozen times—tell her about his ability—but each time it felt like a hollow excuse.

If he stayed here, they would end up hating each other.

And then he did cry. He fell sideways on his bed, covered his head, and sobbed. He grieved for good times that were forever gone. Times never to return. For the pain he’d caused his mother, and the son he could no longer be.

And he cried for those he hadn’t been able to save.

After a time, he fell still. Sleep began to slide over him, but there was no time for rest.

In the darkness of his room, he made a difficult decision.

It was late. Or early. Either way, he had things to do.

He rose and put clothes in a book bag. Enough for three days. He looked around his room at the posters and trophies and treasures that seemed to belong to somebody else. None of it mattered. Nothing in this room mattered to him. He could walk away from it all and be happier.

And so, he did.

He left that night. Returning to the Lusk home, he hid in the bushes. The next morning, he watched through the back French doors as most of the Lusks ate breakfast, gathered their things, and left their home. Becky and a younger brother were the last to leave. The younger brother turned at the last moment and rushed into the backyard. He opened the gate to the pool and grabbed a textbook from a patio table. He ran through the gate and didn’t look back. He left the French door open a crack. Nick watched the whole scene behind a curtain of branches and leaves.

After a time, Nick crept from his hiding place and closed the metal gate to the pool. He returned to his hiding spot and sat down with his book bag filled with clothes. His stomach growled. Forty minutes later a small hand pushed against the open French door and a small child crawled out into the back yard. The baby made his way across the patio until he reached the gate to the swimming pool. He pulled himself up into a standing position and rattled the metal bars.

Nick could see the timer from his hiding place in the shade.

ФФД

ДДД

ФДД

ДДД

ФФФ

ФФД

ДФД

ДФФ

ФДФ

ДФФ

ФДД

Seventy-eight years, and a new red life thread. A person who shouldn’t be here, but was.

And now, Nick needed to find a new place to live.

This dropping back into his life comes at a good time in the story. And gives a better sense of how Nick’s life was before the accident. Especially good touch to have his room with trophies and such so we know he was once son the mom would have been proud of.