Monster: Chapter Twenty-four

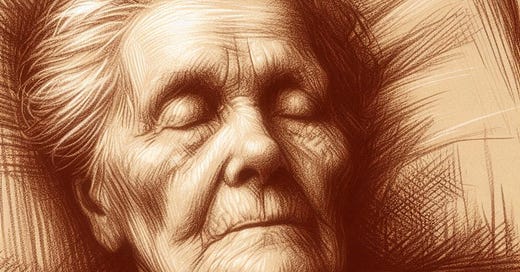

The young may die, but the old must. –Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

Nick paused at the front door of Sunshine Terrace, an assisted living facility in the heart of Logan. Some days he rode his bike, but today he’d walked because it was still below freezing. His tires weren’t up for ice.

He’d been dreading this day for three weeks.

He was no stranger to Sunshin…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Open Author to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.